Reverse Engineering MyDoom.A

April 15, 2022 · 677 words · 4 min

This is a older article I made about taking apart a virus called MyDoom. It was a virus that caused a lot of damage in the early 2000s.

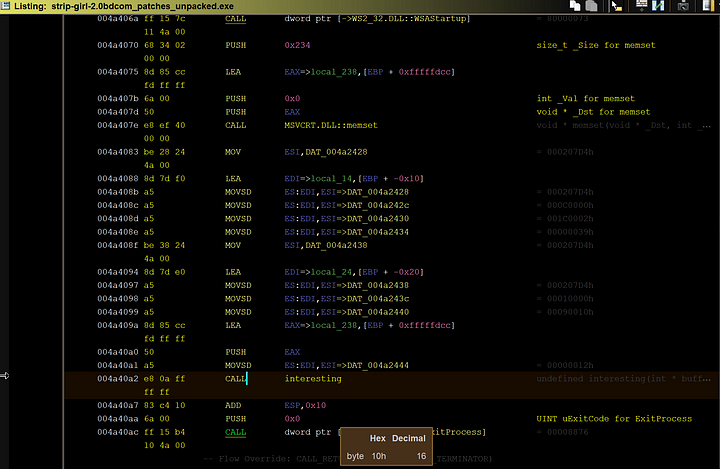

I’ve already relabeled the majority of the functions to better represent what they do. Here we see a function that is called on entry that I renamed to “interesting”. This is where the “main” portion of the code is.

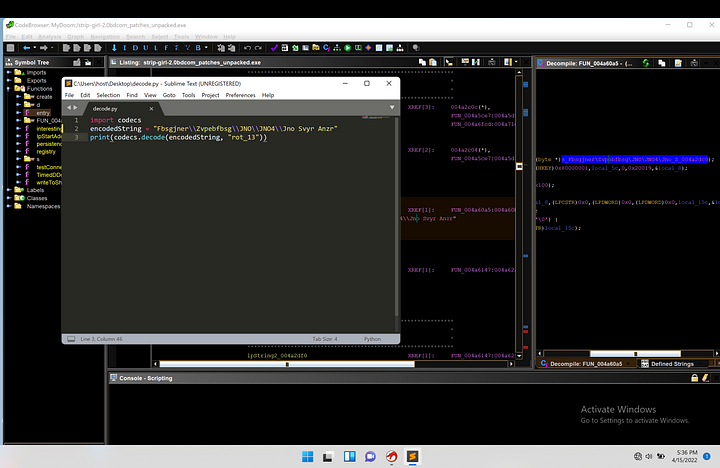

There were certain strings in the program that looked to be encoded in some way. I ended up figuring out that they follow a encoding scheme called “rot_13” which I was able to make a python script that would help decode all of the “interesting” strings.

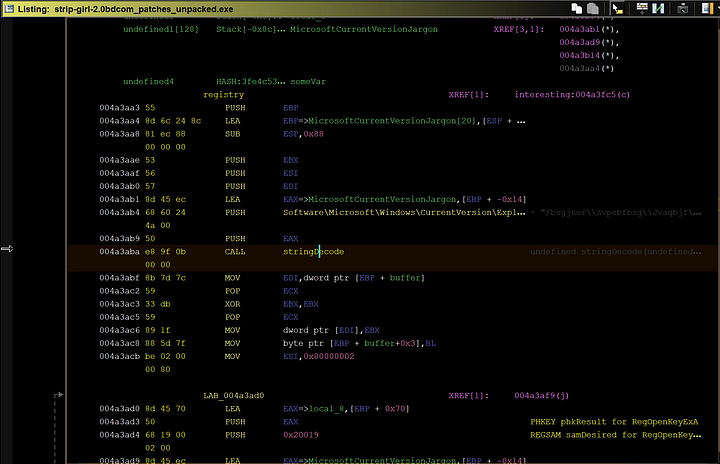

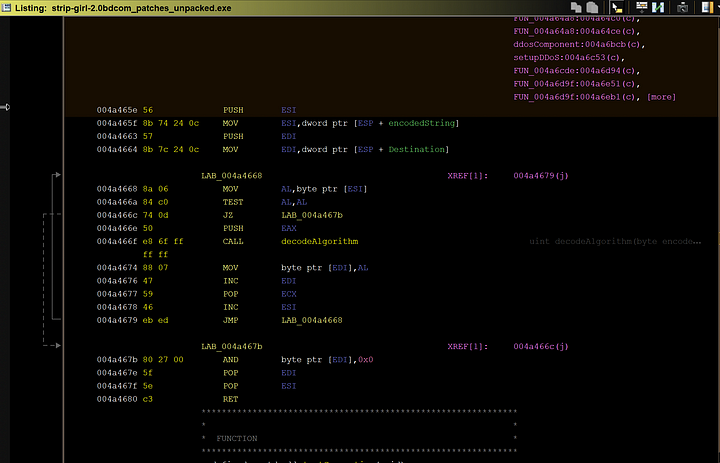

The “stringDecode” function is where the program decodes the previous string in this case “Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion.…”. (Of course, this string in particular has already been decoded as mentioned before)

It then takes a single character from the string and decodes it via “decodeAlgorithm” function. It will then concatenate all of the decoded characters to replace the encoded string.

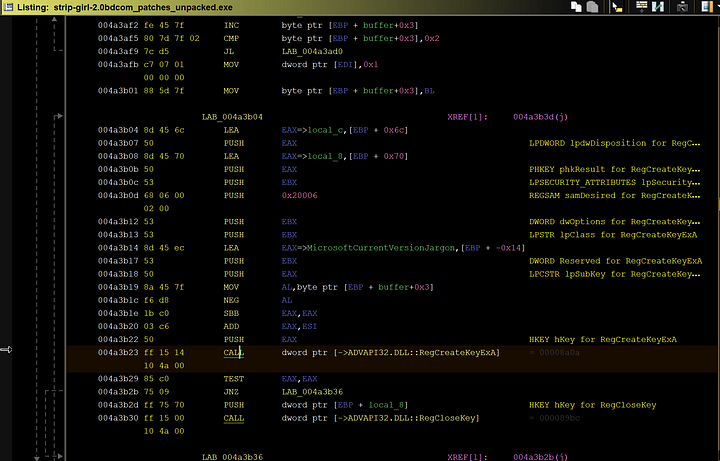

In the registry function, it first decodes its string and then checks to see if the registry key of said string exists and if it doesn’t it will create said registry key. This key may come in handy later down in the programs cycle.

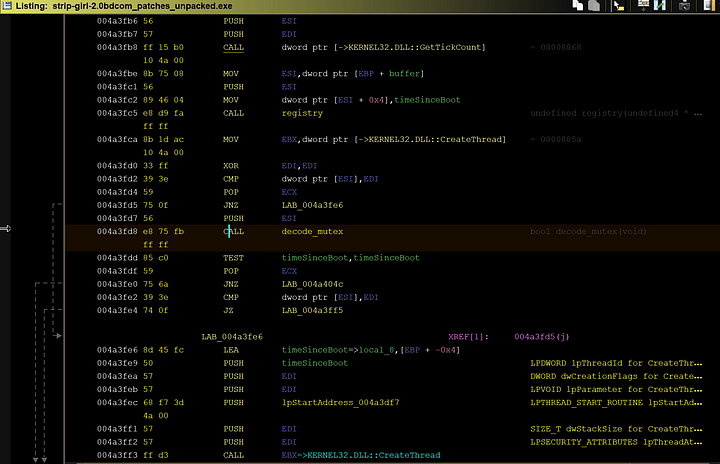

Next up is the decodeMutex function. There isn’t really anything special in this one. This just creates a mutex for the threads the program creates.

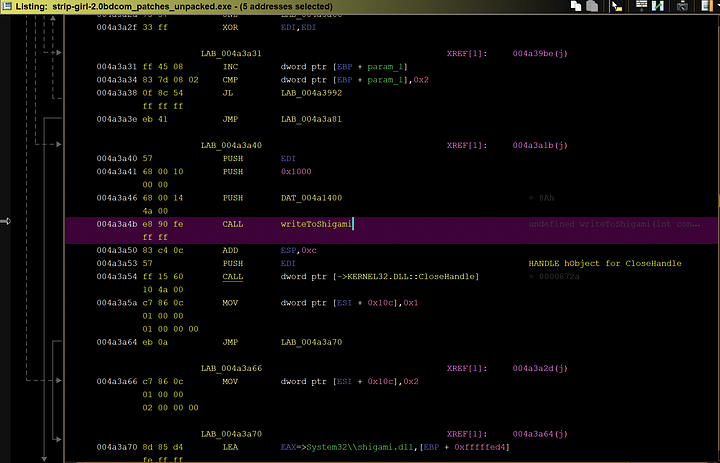

Another feature of this malware is the backdoor that it sets up on the victims machine. Unfortunately, I couldn’t get the DLL file itself onto my machine as I can’t actually run the malware presumably cause of how old it is. We can still analyze the function as is though.

How this function works is that it takes the contents of a certain section of the programs memory and writes it into a new file called shigami.dll. This is the file that contains the backdoor.

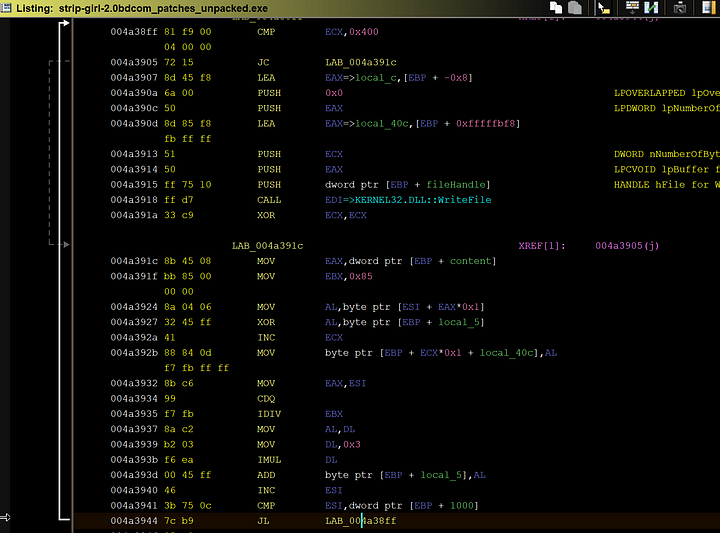

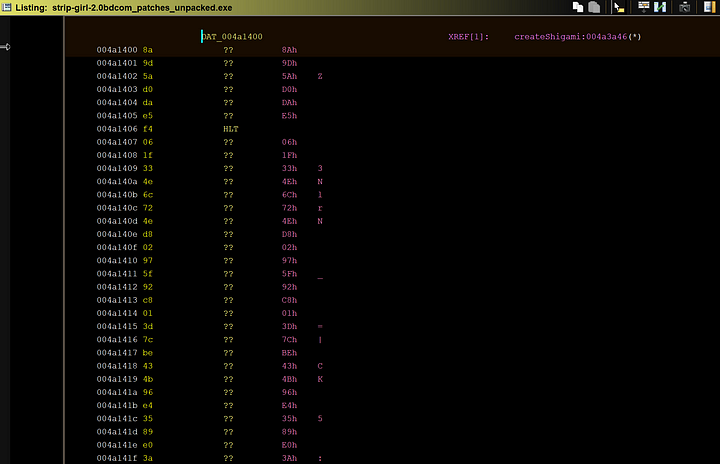

Here is the actual contents of what is being copied byte by byte. In total, over 1000 bytes are copied over to shigami.dll. Which is then stored in System32.

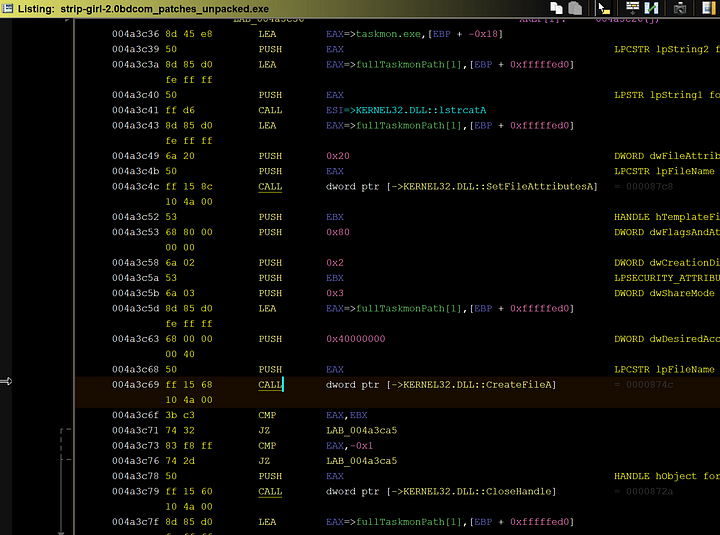

This next function I labeled as “createTaskmon”. This function concatenates multiple strings to develop a full system file path containing “taskmon.exe” at the end of the path. The directory could either be the System directory or the Temp directory depending on certain parameters. “Taskmon.exe” is basically just a copy of this entire malware.

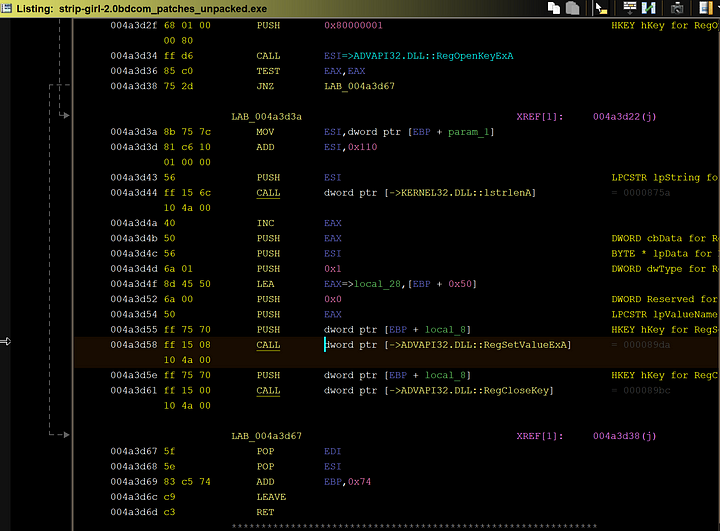

This next function I labeled “persistence” and it is just as it sounds. The virus edits a registry value in the “\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\” to load up on every startup. It adds the “taskmon.exe” from before to ensure this.

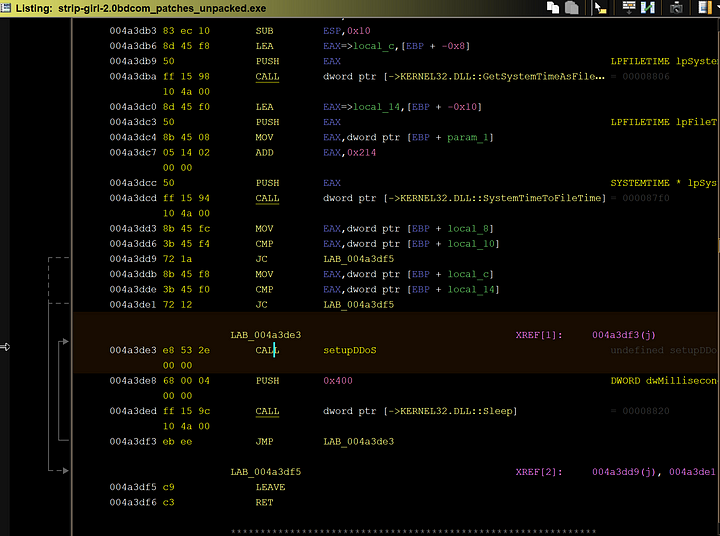

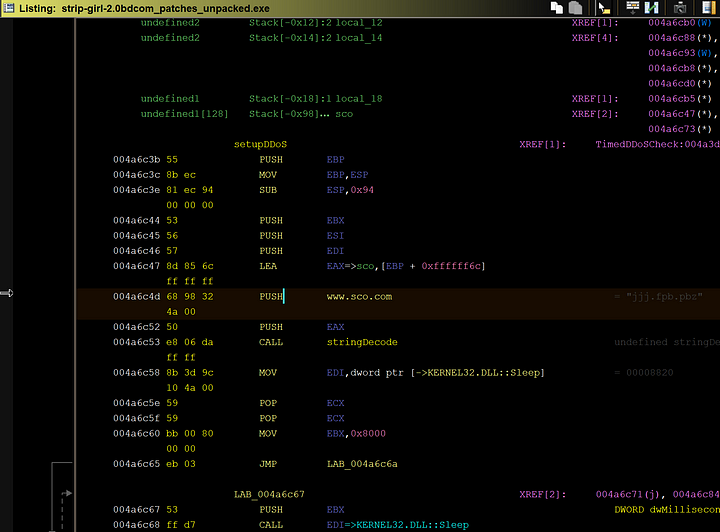

Now we get into one of the juicy bits of the malware, its DDoS capabilities It first checks to make sure that a specific date is met before executing the DDoS attack. This date comes out to being the 1st of February, 2004. Once this date is (was) reached, the malware would execute the next function I labeled as “TimeCheckDDoS” in a while loop.

Here we can see the string of what was the target of the DDoS attack, sco.com.

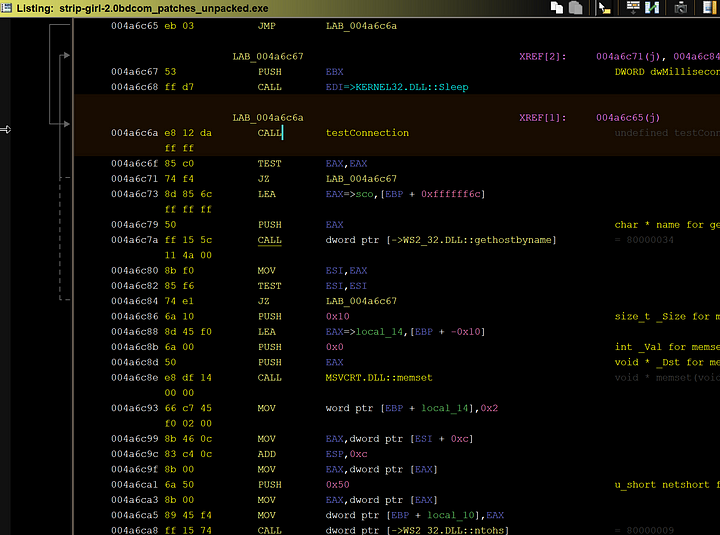

It first makes sure that all the necessary steps to connect to the internet are in place and that www.sco.com is reachable before proceeding with the attack function.

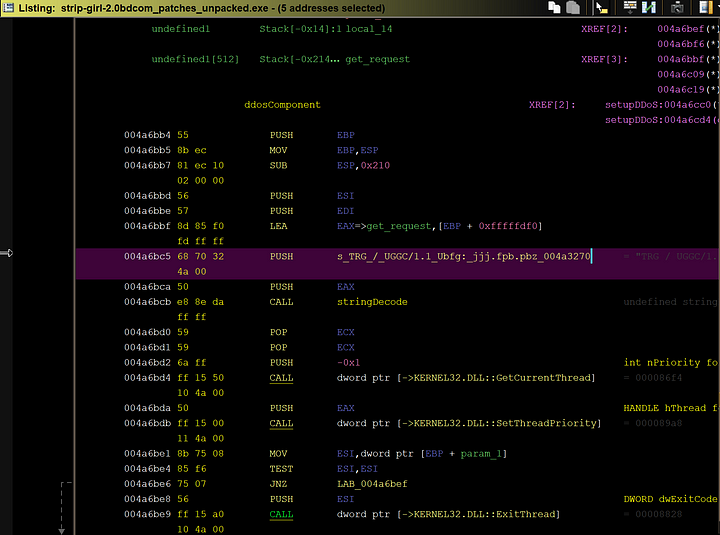

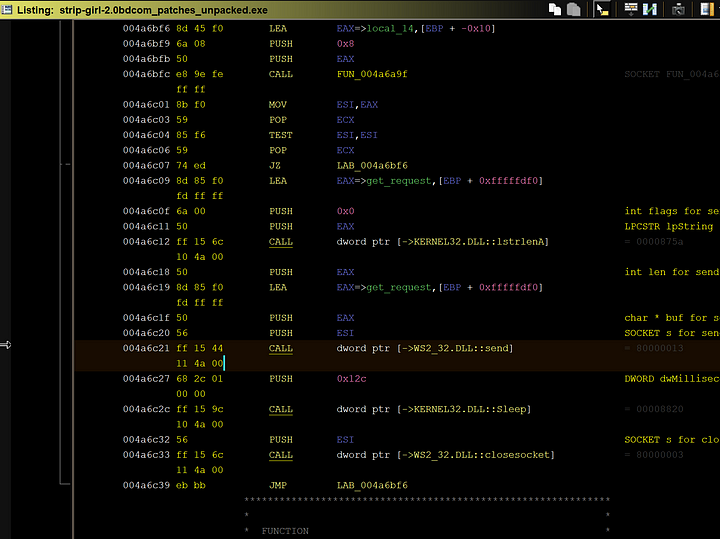

Here in the attacking function we can see the encoded get request that will be sent to port 80 of www.sco.com.

There are 64 threads of this “ddosComponent” function running on one machine, so 64 get requests are being sent in intervals of 1024 milliseconds.

64 get requests from one computer may not seem like a lot, but when scaled to tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of computers all trying to receive the main page of www.sco.com, it’s no wonder that the site was down for months.

This is only the first part of a two part analysis on MyDoom. Part Two will explore how this malware was able to spread as quickly as it did and the mechanisms it deployed to achieve that.